The Rogerian Argument structure

Does man have a right to the Earth and its resources?

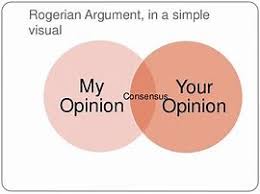

This synthesis research paper must use the Rogerian Argument structure. Rogerian arguments are based

on the assumptions that having a full understanding of an opposing position is essential to responding to it

persuasively and refuting it in a way that is accommodating rather than alienating or antagozing.

Ultimately, the goal of a Rogerian argument is not to destroy your opponents or dismantle their viewpoints

but rather to reach a conclusion that is satisfying to all participants. There is no formalized structure for

the Rogerian argument.

Sample Solution

This paper employs Rogerian argument structure to justify humanity’s right to the earth and its resources. Proponents of the preceding view posit that the Earth sustains life (Adams, 2018). They also perceive contemporary economic crises as a crisis in consciousness and blames humanity for conducting itself as distinct entities from the environment, when, in truth, it is intricately linked to all that is. Consequently, a delusion persists that propagates the belief that land and natural resources should be owned and then profited from by some at the expense of others. While landowners benefit from natural and governmental rewards, the value of land has been subsidized in most places a tacit subsidy which is endemic to the entire system.

Sherlock Holmes, For King and Country

GuidesorSubmit my paper for examination

Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes adventure has delighted in—or now and again, endured—endless rehashes since its unique distribution from 1887 to 1927. The BBC’s present TV form featuring Benedict Cumberbatch is maybe one of the best, not least as its scriptwriters consolidate a profound information on the first with a style for withdrawing cleverly from it: the show’s system of reference, change, and up-to-dateness gives it both newness and recognition. The new arrangement starts with “The Empty Hearse,” its title insinuating energetically to Conan Doyle’s 1903 story “The Empty House” wherein Holmes comes back from evident demise because of Professor Moriarty in Switzerland.

Conan Doyle’s adventure is especially fit to this sort of treatment: the fan-pundits who call themselves “Sherlockians” pore over the subtleties of Dr. John Watson’s accounts (referred to in the exchange as “the Canon”), searching for pieces of information, inconsistencies, and irregularities; they build regularly conspiratorial elective clarifications of occasions, reveal Conan Doyle’s (or Watson’s) clear blunders, and cross-reference the tales with comprehensive grant. Along these lines, while Conan Doyle is frequently observed as a genuinely straightforward essayist, shunning unpredictability, specialized development, and difficulties to standard philosophy for rich fantasy making, the enterprising nature of the Sherlockians shows that the effortlessness of these accounts is regularly beguiling: in a story, for example, “The Empty House,” a lot of significant data is left inferred or alluded to. Recuperating those subtexts through cautious perusing and an information on what else was going on at the time can assist with indicating Holmes and his maker in another light.

“The Empty House” weaves together two stories: a homicide riddle and the narrative of Holmes’ arrival to London, three years after his obvious passing in Switzerland in 1891. Rejoined with his old companion and writer Dr. Watson, Holmes relates the narrative of his getaway at the Reichenbach Falls followed by an exceptional and extraordinary odyssey:

I went for a long time in Tibet, accordingly, and delighted myself by visiting Lhassa, and going through certain days with the head lama. You may have perused of the momentous investigations of a Norwegian named Sigerson, however I am certain that it never happened to you that you were accepting updates on your companion. I at that point went through Persia, glanced in at Mecca, and paid a short however intriguing visit to the Khalifa at Khartoum the consequences of which I have conveyed to the Foreign Office.

These three sentences contain an abundance of references to royal investigation and victory. ‘Sigerson’ is maybe a reference to the Swedish pioneer Sven Hedin, whose earth shattering investigations of Central Asia and the Tibetan level—his discoveries previously distributed in a British and American version in 1903—had started to energize premium and appreciation. In any case, it was another wayfarer of Tibet who was truly standing out as truly newsworthy, and which makes us aware of the settler subtext of the story. By 1903, Francis Younghusband’s “endeavor” to Tibet was going all out. He entered the nation in December 1903 with a power of 10,000 and arrived at Lhasa in August 1904: it was an intrusion in everything except name, the last scene in what Kipling named “the Great Game” where Britain and Russia battled a virus war for control of the Asian terrains that lay between their two realms. Holmes’ quality in Lhasa during the 1890s camouflaged as Sigerson was bound to be perused as basis for Younghusband’s intrusion than unengaged investigation or an extraordinary technique for hiding.

An “Extraordinary Game” clarification may lie behind Holmes’ time in Persia, another object of exceptional Anglo-Russian rivalry: Russia’s expanding financial contribution with the Shah’s system when the new century rolled over was seen with caution in Whitehall and Calcutta as a danger to the boondocks of British India. Mecca, the following port of call, would have required Holmes (who probably had not changed over to Islam) to embrace one of his well known masks, as the British pilgrim and ambassador Sir Richard Burton had done during his endeavor in 1853. Also, Holmes’ ability for camouflage would definitely have been required at his next goal: as he clarifies, Khartoum (or all the more carefully, the neighboring city of Omdurman) was heavily influenced by Abdallahi, the Khalifa, replacement to Mohammed Ahmed, the Mahdi during the 1890s.

The Khalifa and his state in Sudan, the Mahdiyya, held a comparative situation in the late-Victorian awareness as the Taliban and Al Qaida do today. The Mahdiyya’s powers had been answerable for a portion of Britain’s most unfortunate military annihilations of the 1880s, driving in the long run to the affliction of General Charles Gordon, whose representation, we are told in ‘The Adventure of the Cardboard Box,’ hangs in 221b Baker Street. In 1897, Conan Doyle was certify as a columnist for the Westminster Gazette to go with Herbert Kitchener’s endeavor into Sudan to clear out the Mahdiyya, in spite of the fact that his news-casting was a sorry achievement, as he was told by Kitchener actually to return home. By and by, Conan Doyle’s dispatches for his paper uncover an eager help for Kitchener’s undertaking which peaked in 1898 with the Battle of Omdurman, in which 10,000 of the Khalifa’s powers were killed surprisingly fast by the British and Egyptian militaries (which themselves endured a minor 47 fatalities).

In “The Empty House,” at that point, Conan Doyle composes of the period before Omdurman, yet with the information on its result. Holmes’ easygoing reference to speaking with the Foreign Office just appears to affirm what has just been flagged: he has gone through the three years after his getaway at Reichenbach not only escaping Moriarty’s partners in crime, yet working stealthily for the British Empire.

Holmes comes back to London to illuminate the homicide of the Honorable Ronald Adair, a ‘bolted room secret’ in which a youthful blue-blood is discovered shot dead in his upstairs parlor, bolted from within, at 427 Park Lane. The window is open, however there are no signs that anybody could have entered through it; there is no weapon, yet on the table close to Adair are heaps of gold and silver coins, a few banknotes, and a piece of paper bearing names and numbers. We are informed that Adair invested the vast majority of his energy playing a game of cards in different London clubs, and the names on the paper are of individual players. We are additionally informed that his commitment to his life partner has quite recently been severed, and that he and his companion Colonel Sebastian Moran had as of late won a huge whole at cards from Godfrey Milner and Lord Balmoral.

Holmes’ earlier information seems to settle the riddle. He realizes that Colonel Moran is in actuality one of Professor Moriarty’s associates and “the second most risky man in London.” He traps Moran by setting a wax sham (moved at interims by Mrs. Hudson) in the window of his rooms in Baker Street; he, Watson, and Inspector Lestrade look on as Moran takes his situation in an unfilled house with a view to the window, points his German-made air-rifle adjusted to take delicate nosed slugs, and shoots the wax sham. Lestrade captures Moran as the killer of Ronald Adair.

The personality of Adair’s killer flags another part of the story’s magnificent subtext. Colonel Moran has entered the universes of tip top recreation (high-class betting) and world class wrongdoing (Moriarty’s group) from a foundation in Her Majesty’s Indian Army where he was, Holmes uncovers, “the best overwhelming game shot that our Eastern Empire has ever created,” acclaimed for following tigers in the wilderness: Holmes considers him an “old shikari”— a Urdu word for tracker. Like Watson, he has served in Afghanistan (not at all like Watson with so much qualification as to be referenced in dispatches), and he has realm in the blood: his dad was a previous British Minister to Persia. Watson is surprised by this present rebel’s experience as a “good officer,” provoking Holmes to conjecture that Moran’s “unexpected turn” to detestable is the aftereffect of some acquired hereditary marker.

There are numerous charming subtexts in this secret—tension about the ramifications of Germany’s mechanical superiority, trendy speculations of degeneration—yet the one to concern us here is Moran’s faultless armed force record. This story is partially an investigation into how and why at first good men of realm may turn out to be rotten ones. A few hints inside the content recommend that Conan Doyle had a genuine case as a main priority. Approached by Watson for Moran’s thought process in slaughtering Adair, Holmes’ answer relies on hypothesis that Moran was cheating at cards and this had been found by Adair: “likely he had addressed [Moran] secretly, and had taken steps to uncover him except if he intentionally surrendered his enrollment of the club, and vowed not to play a game of cards once more.” Rather than give such an endeavor, Holmes estimates: Moran killed Adair.

Here the story has all the earmarks of being insinuating one of the greatest highborn outrages of the earlier decade. What was known as “the Baccarat Scandal” or “the Tranby Croft issue” had fixated the Victorian paper perusing open when it went to the High Court in 1891. A Lieutenant-Colonel in the Scots Guards, Sir William Gordon-Cumming, had been blamed for cheating at baccarat—a variety of boat or vingt-et-un with a financier, two players, and two gatherings of spectators wagering on whose hand is nearest to nine—by his hosts and some kindred previous armed force officials during a highborn gathering at Tranby Croft in Yorkshire in September 1890. Gordon-Cumming, a baronet and significant Scottish landowner who had battled with extraordinary qualification in the Zulu War, and the Egyptian and Sudanese Campaigns (counting at the clash of Abu Klea in 1884 as a component of the destined strategic